Ingredient brands are product components that not only add functional value, but their logo on a main branded product or service also adds to its own brand power to retain customer loyalty, evoke customer preference, and support premium price points. An ingredient brand not only adds value to the host brand’s equity, but in mature markets, it can also create or enhance differentiation.

Intel® is arguably the most famous of all ingredient brands that has enjoyed a long and continuing life. Others include Microban®, Kevlar®, and Goretex®.

The Birth of an Ingredient Brand

When an upstream manufacturer develops a new breakthrough product, they diligently commercialize and promote its identity in order to increase the market’s acceptance of the product. Since the branded product is a breakthrough, it is accepted by direct customers and often becomes famous for the benefits it brings to the downstream market. When promoted properly, it also becomes desirable to consumers, because of the publicity it generates as a source of “new” perceptions for older brand names that incorporate it into their product lines.

The name the manufacturer gives the product is generally intended to simplify conversations with specifiers, product managers, and others whose beliefs in the product’s value prompt them to include it in production processes, and to assist purchasing agents in requesting the right product. Most often, this value is discussed in terms of how the product is functionally advantageous. This is common practice in industry. However, the product’s value as a public indicator of the host brand’s commitment to quality innovation should not be overlooked.

As a new ingredient brand becomes familiar among downstream specifiers, the name not only becomes more recognizable, but also develops its own meaning. The ultimate constituency that fosters an iconic meaning for any brand is consumers who assign daily-life significance to it. At that point—when a labeled component of an end product like a computer or fashionable garment becomes a familiar name that influences consumers’ choices—an ingredient brand is born.

Strong host brands often hesitate to publicly identify an ingredient brand due to concerns about compromising their own brand’s perceptions. History has shown, however, that a powerful ingredient brand whose provider is committed to maintaining its perceptual equity long term continues to be enhanced by identifying investment in publicly recognized quality components. Smart host branders take full advantage of the popularity of a famous ingredient brand, further enhancing the equity of their original brand.

Challenges of Managing an Ingredient Brand

Many ingredient brands, such as Intel®, Kevlar®, Micro-Ban®, and Stainmaster®, have successfully passed the value-adding test of time. The key to achieving this marketplace status is to manage the ingredient brand well beyond its functional value. Accomplishing this is much more complex than managing a consumer brand. Ingredient branders face their own challenges that must be met in order to fully capitalize on an ingredient brand’s value potential.

Develop organizational understanding of the difference between the product and the brand to multiple constituencies, each with their own mindset and calculation of interest.

Effectively communicate the brand downstream from the direct customer, without creating unmanageable friction with that customer, who may perceive the ingredient brand building effort as inevitably reducing their profit margins.

Educate their own leadership on the value of creating and maintaining brand equity and the need to market the brand benefits that exist beyond its functional contribution to product features.

Educate the host brand’s leadership on value of brand equity and the need to market the brand benefits beyond the product features.

Articulate an integrated marketing strategy, with a balanced emphasis beyond product performance value, to include benefits and emotional brand image that drive differentiation and preference, and implement it consistently overtime.

Coordinate all management functions to contribute to consistent brand message—to “walk the brand talk” in all decisions.

Assure that the internal organization, channel organizations, and customers always use the brand icon and extensions correctly. They must police misuse of the brand by others or risk commoditizing the brand and diminishing its financial value to that of a generic.

Capture and retain price premium, avoiding the temptation to trade off long-term premium for short-term share.

Gain and maintain organizational commitment to improving product performance that is consistent with what the brand means to members of its value chain and end users.

Brands have life cycles that operate somewhat differently than product life cycles. Both product and brand lives have “youth,” “maturity,” and “old age.” Unlike humans, product and brand lives can be rejuvenated and returned to their “youth”—usually renewed relevance accomplished by capitalizing on new end user trends. The classic example is Maytag, whose “dependability” positioning in the 1930s reassured homemakers that the new-fangled electric motor eliminating women’s hours at a washboard was going to last. By the 1970s, this was irrelevant, and Maytag lost consumers’ attention.

The arrival of the “lonely repairman” renewed the relevance of Maytag’s dependability to homemakers who now worked at jobs out of their homes full time and whose faulty washer might cost them a day of work. Maytag shows the opportunity careful management of a branded product’s life cycle offers.

Brand Management Life Cycles

The “marketing triangle” highlights managing the three critical dimensions of marketing a brand today: product, brand, and price. In the typical marketing triangle, the marketer develops and commercializes the breakthrough product and, after the product begins to achieve a high level of recognition, begins the process of branding the product. Instead, the marketer should recognize the brand potential of the breakthrough product and initiate brand management process immediately upon commercialization. An operating comparison of these two approaches is described below.

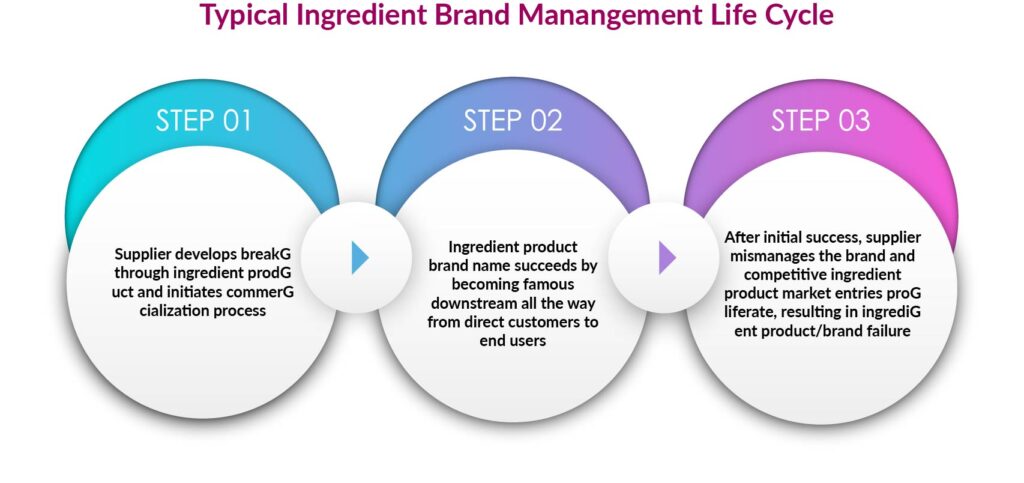

The Typical Brand Management Cycle

In the typical approach, the supplier develops and commercializes the breakthrough product and, after the product becomes famous, begins to transform the product into a brand.

Step 1 — Supplier develops breakthrough ingredient product and initiates commercialization process.

- Supplier demonstrates value-added potential of the new ingredient product and sets price based on benefits offered—including potential for furthering host brand differentiation in its own market.

- Supplier expands acceptance from early adopters among host brand products to early majority of host brands in a given product category.

- Ingredient brand management team makes a public commitment to investing in the promotion of their own brand, offering promotional value to host brands that feature the ingredient product.

- Supplier effectively positions the ingredient brand with communications that converge on its central benefit—articulated to each member of the main product’s value chain.

- Ingredient brand name becomes well known and universally used across industry applications.

- Ingredient brand acquires meaning from positioning communications combined with satisfactory or superior experience among value chain members and end users of the main product brand.

- Ingredient brand is perceived as critical to fulfilling expectations generated by marketing efforts of the host product brand.

Step 2 — Ingredient product brand name succeeds by becoming famous downstream all the way from direct customers to end users.

- Multiple members of the value chain specify the product by name.

- There is increasing consumer awareness and evidence that the ingredient brand encourages host brand preference and loyalty.

- Supplier makes the shift from generic ingredient product to named ingredient brand.

- Price premium is maintained, even though competitors enter with similarly performing products.

- Perceptions of ingredient brand promise and meaning add value to functional advantages, signifying such benefits as quality assurance and functional performance advantage in production processes, as well as end user experiences.

Step 3 — In typical scenarios, after initial success, supplier mismanages the brand, and competitive ingredient product market entries proliferate.

- Internal stress on the ingredient brand’s product renewal activity and on pricing result in temptation to rest on early success.

- Direct customers exert downward pressure on brand price based on competing alternative products.

- Ingredient brand fails to counter with continued efforts to build perceptions of the brand’s superiority beyond functional features in the minds of value chain members and end users.

- Accepting market definitions of function-only brand fosters downstream indifference over time.

- Ingredient brand decays in product quality in order to keep plants operating at capacity (planned or unplanned) at diminished market prices.

- Management declares ingredient branding a failed marketing strategy.

The Successful Ingredient Brand Management Life Cycle

Step 1 — Supplier develops a breakthrough ingredient product and initiates the commercialization process as in the previous case, BUT includes brand planning from the start.

- Value is demonstrated in terms of how the direct and downstream customers benefit from the start of brand naming the product. Thus, the ingredient product is translated into a brand at the time of commercialization.

- The new ingredient brand is effectively positioned relative to the value it brings to each member of its value chain. It will establish a core value on how it will do business, but will emphasize the most relevant benefits it promises for each member of its value chain and each end use application it can serve.

- Value chain and end user constituencies needs are inventoried via customer research during the marketing strategy development process.

- Brand support is provided to both the direct and downstream customers.

Step 2 — Product branding strategy is initiated and simultaneous with the commercialization.

- The brand, rather than the product, becomes the primary communication tag. All interactions associate the brand’s name and relevant value to the specific situation and audience.

- An icon is developed and displayed profusely in every communication vehicle. Emphasis is on brand benefits based on what the brand does, not what it is. The use of the icon by host brands is mandated, and parameters are described in legal agreements with host brands.

- The brand essence is defined and communicated along with the brand name and icon—either explicitly in promotion efforts or implicitly by choice of associations where the ingredient brand appears. Brand meaning is a factor in choosing host brand partners.

- Orders are for the ingredient brand, and invoices reflect the brand as an integral aspect of purchase.

- Direct and downstream customers refer to the brand, use the brand icon, and charge a premium for their branded products that incorporate the ingredient brand.

Step 3 — Brand is priced to value and never price-point compared to competitive products.

- Brand is specified by downstream customers.

- Early adopter direct customers are given preference and provided with unique brand and product support.

- Cooperative marketing campaigns are designed uniquely to each customer.

- Cooperative marketing campaigns are designed with downstream customers who see value in the brand.

- Ingredient brand value increases with the number of valued host brand relationships and the satisfaction of value chain members and host brand partners in how the ingredient brand aids their business development—either directly or via ingredient brand support programs (e.g., co-op promotions, design resources made available only to host brand partners, etc.).

Convert the Typical Model to the Successful Model

Begin with brand management in mind. Apply a branding mindset at the onset of product commercialization, including naming, icon development, brand positioning, and communications. When doing the market validation concept research early in the product concept phase, design it to not just learn what end user respondents like or dislike about the concept, but also to capture how the respondents talk about the concept. This aspect of the data will inform your marketing team about how best to position it and help your brand communications team develop its most compelling messages.

Ingredient Branding Insights

Latest Insights

Trust Signals in Regulatory-Heavy Markets

Ingredient branding in regulatory-heavy markets builds visibility and trust through verified trust signals and compliance transparency.

R&D Branding: A Hedge Against Uncertainty

Embed branding into R&D to transform innovation into market-ready trust signals, reducing risk and accelerating go-to-market strategy in uncertain times.

Value Chains in Motion: Ingredient Branding During M&A Transitions

Learn how ingredient branding preserves brand equity, alignment, and trust signals during M&A transitions across global value chains.